Polar Ice Cores, Part 3: Variations in Greenhouse Gases

Carbon dioxide levels are now the highest in many millions of years, reaching values never before encountered by humans

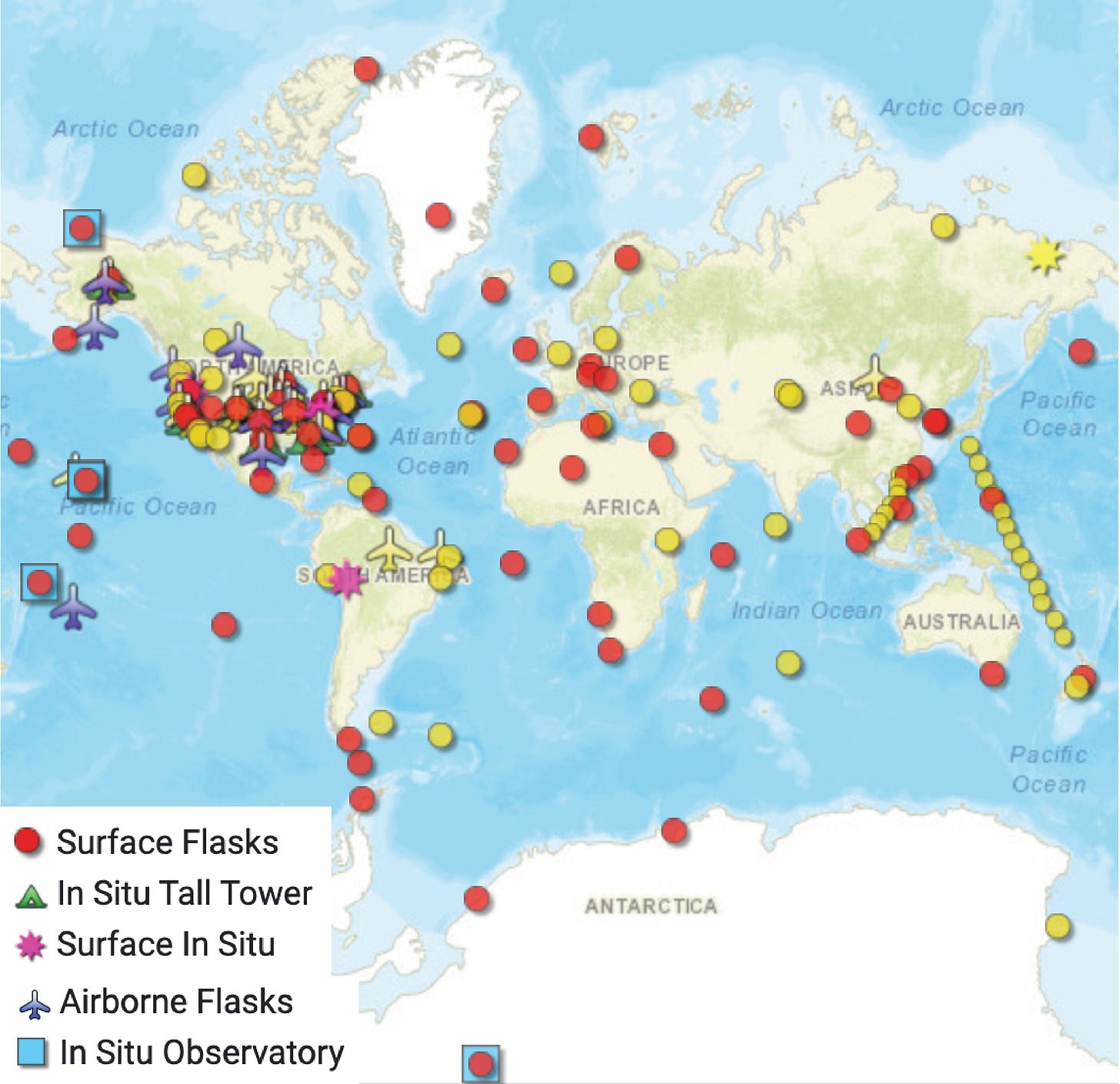

Unbeknownst to many people, a small team of scientists has been continually collecting air samples from all over the world - week after week for many decades - from a globally distributed network of sites. The network is known as the NOAA/ESRL/GML CCGG cooperative air sampling network, an effort that began in 1967 at Niwot Ridge, Colorado to better understand greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Maintaining this network is no small feat, as some sites are often very remote, a necessity for the types of measurements being made.

Some of the sites include:

Arembepe, Bahia, Brazil

Alert, Nunavut, Canada

Anmyeon-do, Republic of Korea

Ascension Island, United Kingdom

Assekre, Algeria

Terceira Island, Azores, Portugal

Baring Head Station, New Zealand

Bukit Kototabang, Indonesia

Tudor Hill, Bermuda

Cape Grim, Tasmania, Australia

Christmas Island, Republic of Kiribati

Cape Point, South Africa

Easter Island, Chile

Mariana Islands, Guam

Halley Station, Antarctica

Harvard Forest, Massachusetts

Hegyhatsal, Hungary

Storhofdi, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland

Izana, Tenerife, Canary Islands

Key Biscayne, Florida

Gobabeb, Namibia

Mahe Island, Seychelles

Cape Kumukahi, Hawaii

Niwot Ridge, Colorado

Shemya Island, Alaska

Southern Great Plains, Oklahoma

Tambopata, Peru

Tutuila, American Samoa

Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, United States

Lampedusa, Italy

Pallas-Sammaltunturi, Finland

Ragged Point, Barbados

Palmer Station, Antarctica

Mahe Island, Seychelles

Ulaan Uul, Mongolia

Mt. Waliguan, China

Ny-Alesund, Svalbard

South Pole, Antarctica

Summit, Greenland

Tae-ahn Peninsula, Republic of Korea

Moody, Texas, United States

Ketura, Israel

Trinidad Head, California, United States

Taiping Island, Taiwan

Ushuaia, Argentina

Mauna Kea, Hawaii

Mauna Loa, Hawaii

I think I am going to adopt the above sites as my life-long bucket list for travel! Amazing.

At the sites listed above (and others), atmospheric air samples are collected and shipped to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for “analysis of carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen gas (H₂), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆); and to the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR, University of Colorado) for the analysis of stable isotopes of CO₂ and CH₄ and for many volatile organic compounds such as ethane (C₂H₆), ethylene (C₂H₄) and propane (C₃H₈). Measurement data are used to identify long-term trends, seasonal variability, and spatial distribution of carbon cycle gases.” Among other results, the data presents unequivocal evidence that the climate is changing because of human activity - this will be the topic of a future newsletter.

The NOAA/ESRL/GML CCGG cooperative air sampling network. Today, the network is an international effort which includes regular sampling from baseline observatories, cooperative fixed sites, towers, commercial ships, and airplanes. An interactive data viewer is available, for example, here for Easter Island, Chile.

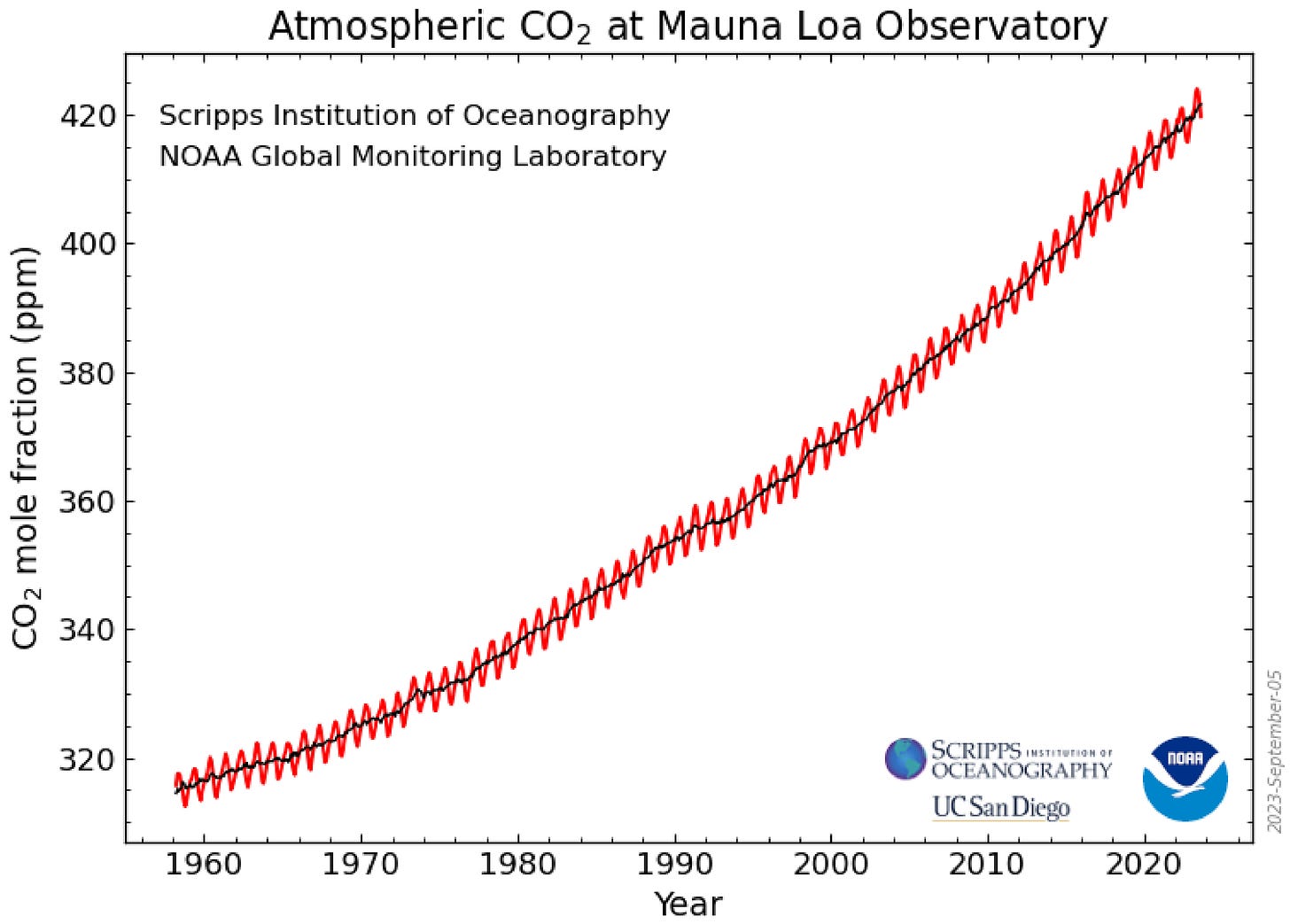

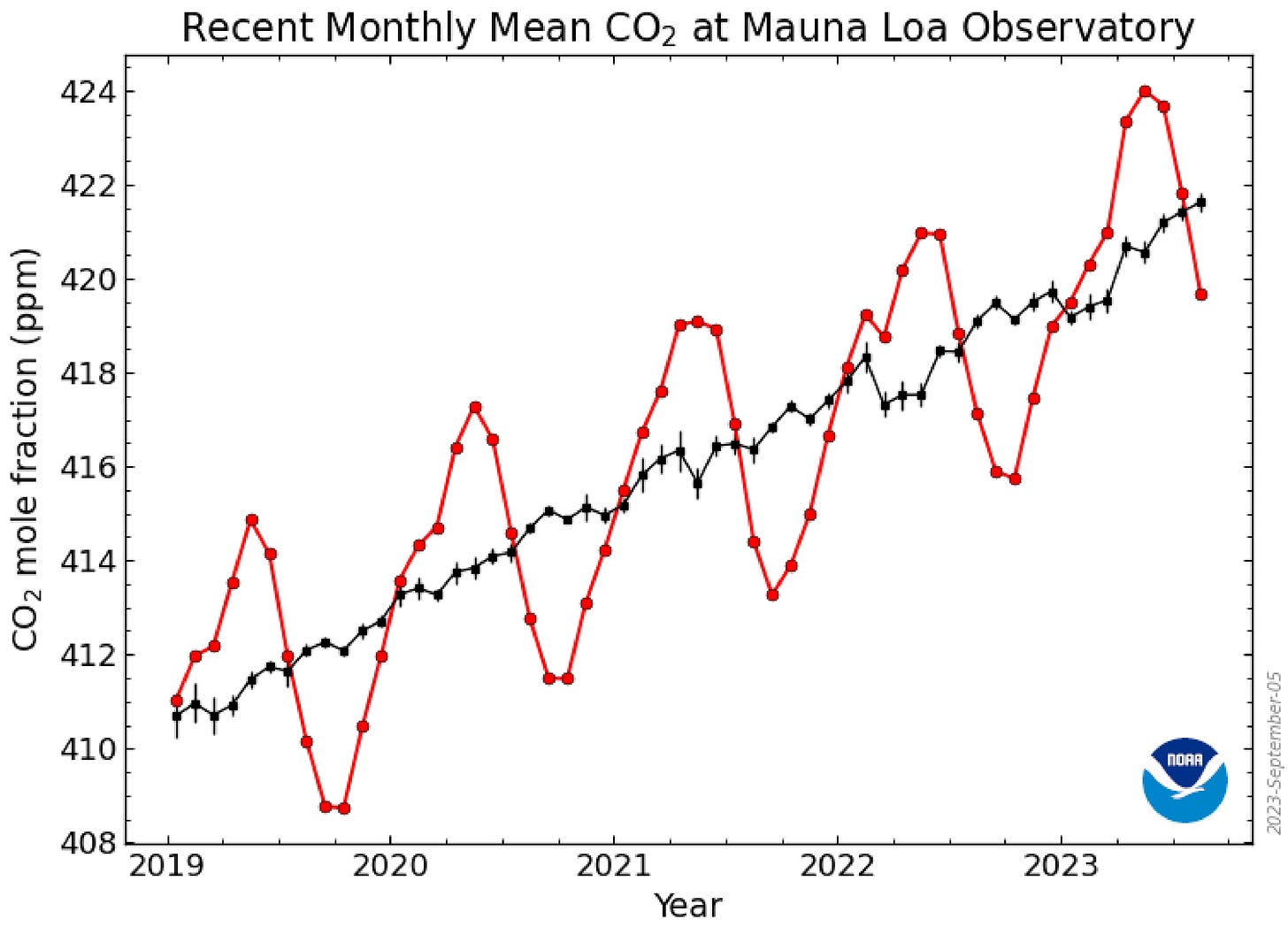

The most iconic and longest individual record of atmospheric greenhouse gases is the carbon dioxide (CO₂) record from Mauna Loa, Hawaii, also known as the Keeling Curve. This record was started by geochemist Charles David Keeling of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1958. NOAA started its own CO₂ measurements in May 1974, running in parallel with Scripps ever since. The record has been interrupted only a few times, once in 1964 for three months due to federal budget cuts, another time in 1984 for about a month when the Mauna Loa volcano erupted, and most recently from December 2022 through July 2023 when the volcano erupted again and cut off power to the station. Observations during this recent shut down were instead made from a nearby station called Maunakea Observatories, approximately 21 miles north of the Mauna Loa Observatory.

A graph of carbon dioxide (CO₂) measured at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii. The red line represents monthly mean values, centered on the middle of each month. The black line represents the same, with the seasonal cycle removed. More information about how the data is measured can be found here and here, and an explanation of the CO₂ cycle is briefly discussed here, which mentions: “There is a clear seasonal cycle in atmospheric CO₂ as plants photosynthesize during the growing season, removing large amounts of CO₂. Respiration (from both plants and animals) and decomposition of leaves, roots, and organic compounds release CO₂ back into the atmosphere.” The global CO₂ seasonal cycle is weighted towards processes occurring in the Northern Hemisphere because there is more land mass. [NOAA, Public Domain]

The last 5 years of CO₂ data from Mauna Loa Observatory (and Maunakea Observatories during the shut down), reaching a high value of about 424 parts per million (ppm). [NOAA, Public Domain]

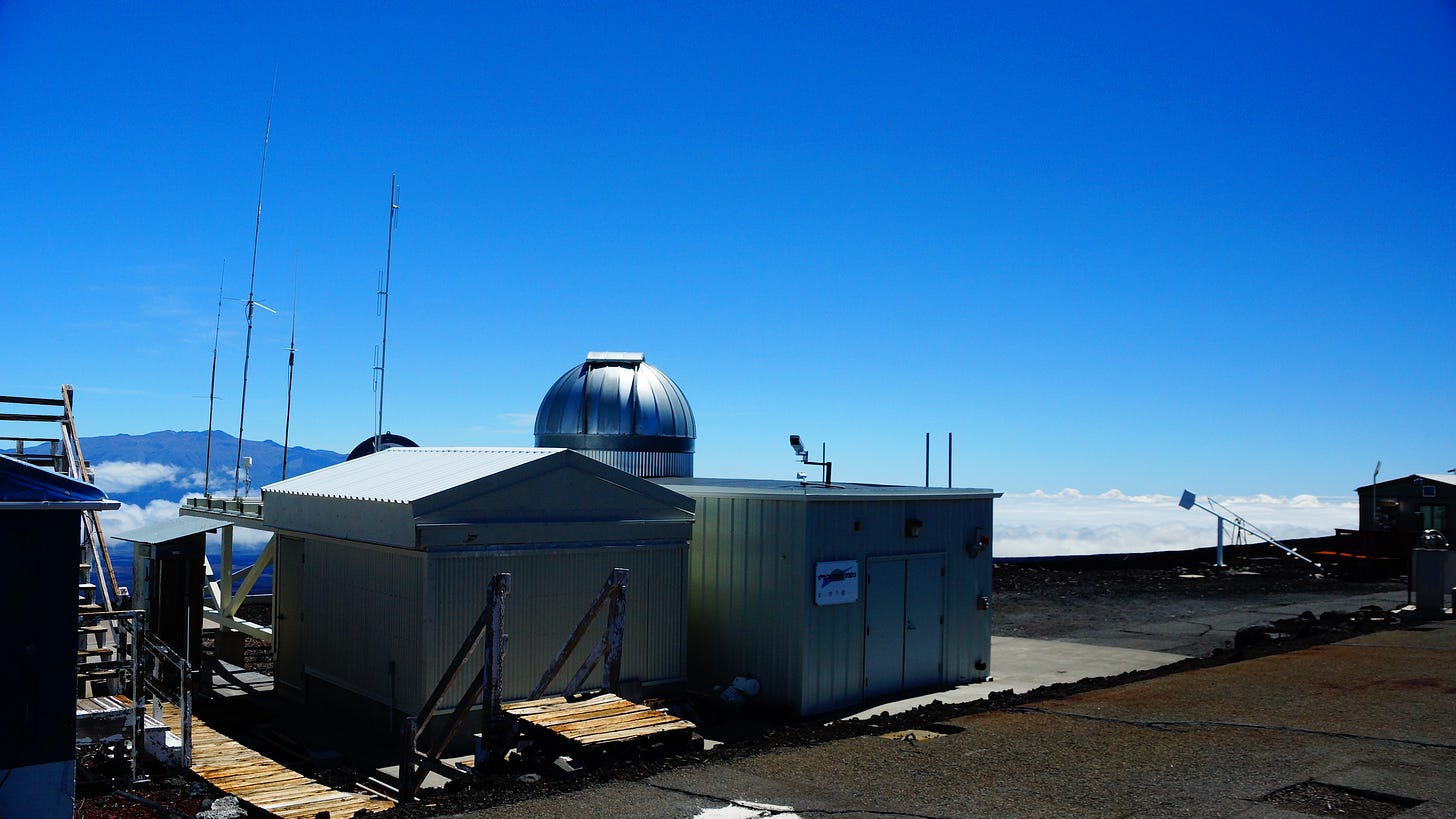

The Mauna Loa Observatory sits at an altitude of 3,400 m (11,150 ft), often enjoying views high above the clouds on the main island of Hawaii. The Observatory is an ideal site to measure “background” values of atmospheric greenhouse gases, away from centers of human activity. The drive to Mauna Loa Observatory, from sea level to 11,150 ft, can be done by anyone and is considered one of the great day adventures by car on Earth. [photo credit: NOAA/Susan Cobb, Public Domain]

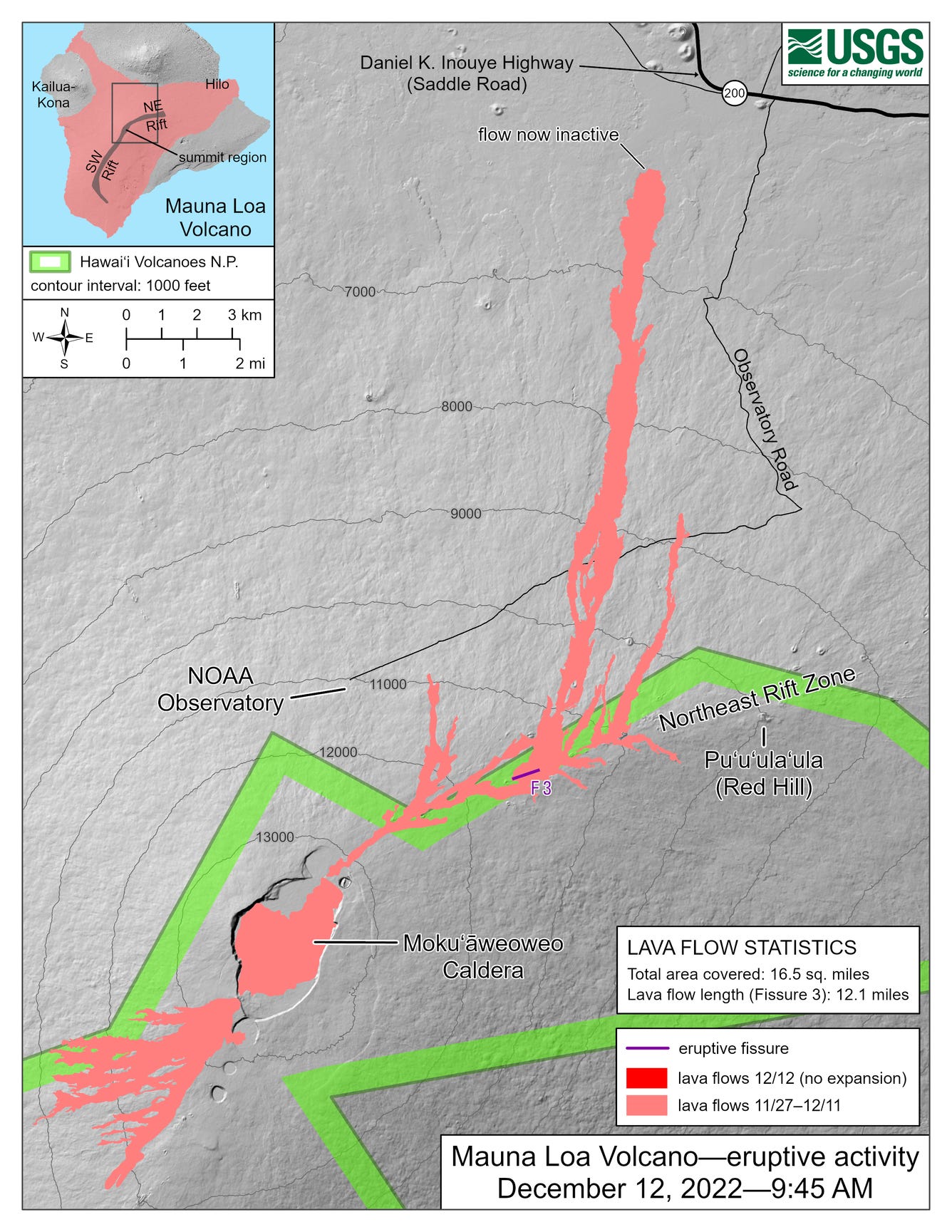

The 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa produced lava flows that came close to the Mauna Loa Observatory, which ended up being shut down for many months, partly due to loss of access via Observatory Road. [USGS Map, Public Domain]

Fissure 3 on Mauna Loa produced lava fountains 100 to 200 feet in height. [National Park Service, Public Domain]

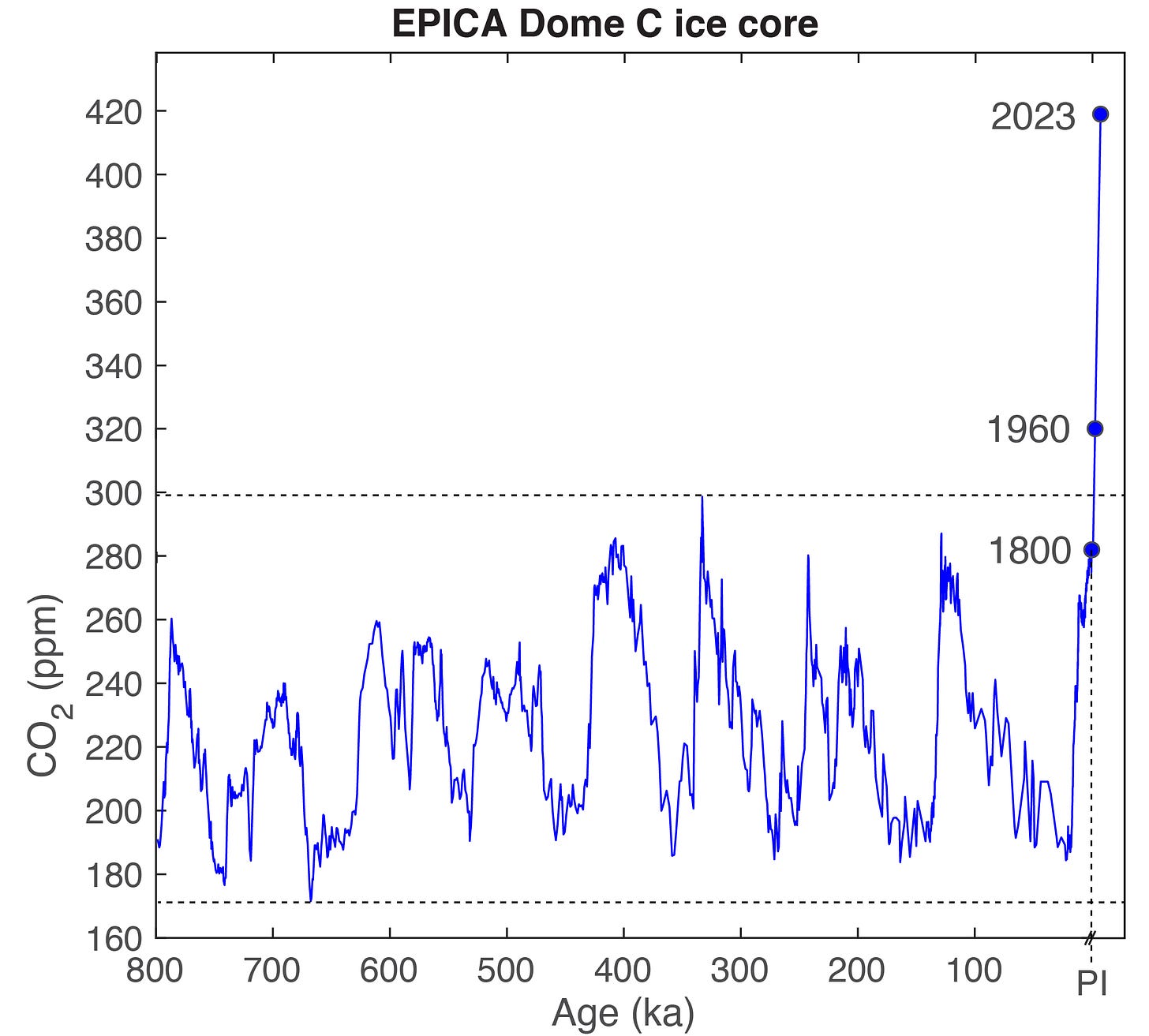

Now, let’s dive further into the past. The best records we have of past CO₂ - before instrumental records like Mauna Loa began - are in trapped air bubbles found in ice cores in East Antarctica (see plots below). Absent human-caused emissions, the natural envelope of atmospheric CO₂ across ice-age cycles for the last 800,000 years (and probably for at least the last 2.7 million years) was about 170 - 300 parts per million (ppm). In the year 1800, just before human-industrial activity began to ramp up, atmospheric CO₂ was about 283 ppm. By 1960, CO₂ had reached 320 ppm, and at the writing of this newsletter in 2023, we have reached 421 ppm on average. A value of 421 ppm is unprecedented in the last 3.6 million years, and is the highest value that humans have ever encountered over the course of our evolution, which started with the emergence of Homo erectus (upright man) in the fossil record about 1.9 million years ago.

Plot of carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) Dome C ice core from East Antarctica, extending over the last 800,000 years (the ‘ka’ on the x-axis refers to ‘thousands of years before present’). Data since 1960 is from NOAA/Mauna Loa Observatory. The PI refers to “pre-industrial”, the time just before human-industrial activity began around the year 1800. The dotted lines represent natural variability in the climate system (CO₂ ranging from 170 to 300 ppm), prior to human activity. In the year 2023, CO₂ reached 421 ppm, and is steadily climbing unabated. Note that older ice-core CO₂ data extending to 2.7 million years before present is discussed in this Science article. [data: NOAA; plot: Tyler R. Jones, CC BY 4.0]

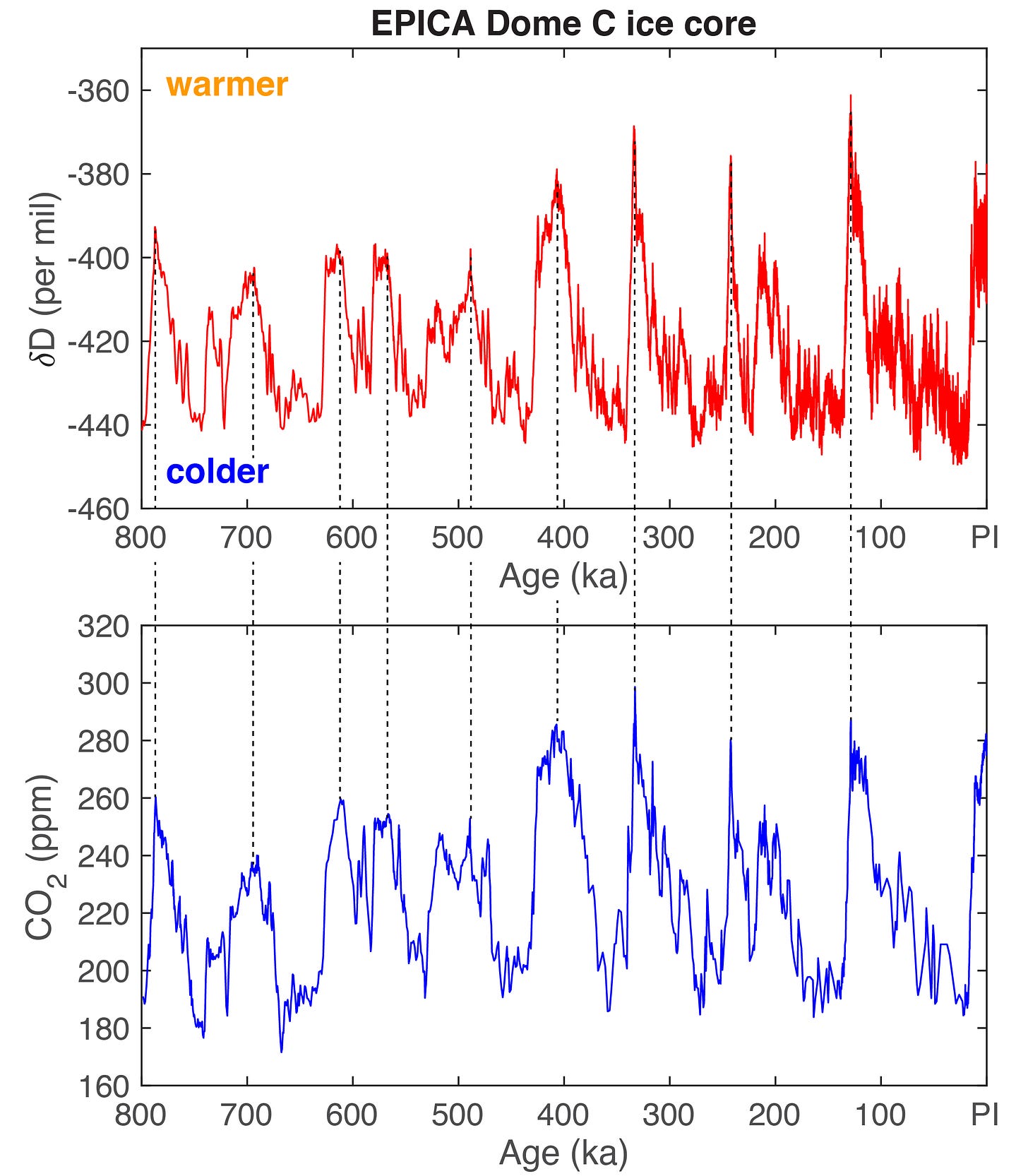

(Top) A record of hydrogen isotopes (δD) from the EPICA Dome C ice core. The δD measurement can be considered a proxy for local temperature. (Bottom) The record of carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the EPICA Dome C ice core. There is a 1:1 correlation between long-term variations in temperature and CO₂, as expected from the greenhouse effect. [data top: Pangaea; data bottom: NOAA; plot: Tyler R. Jones, CC BY 4.0]

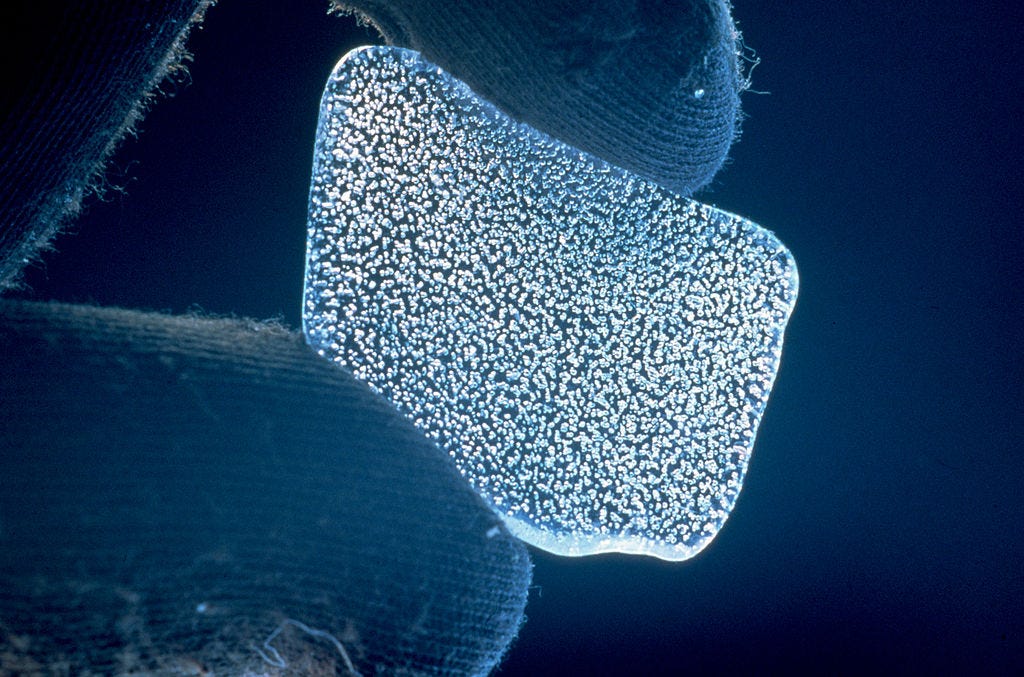

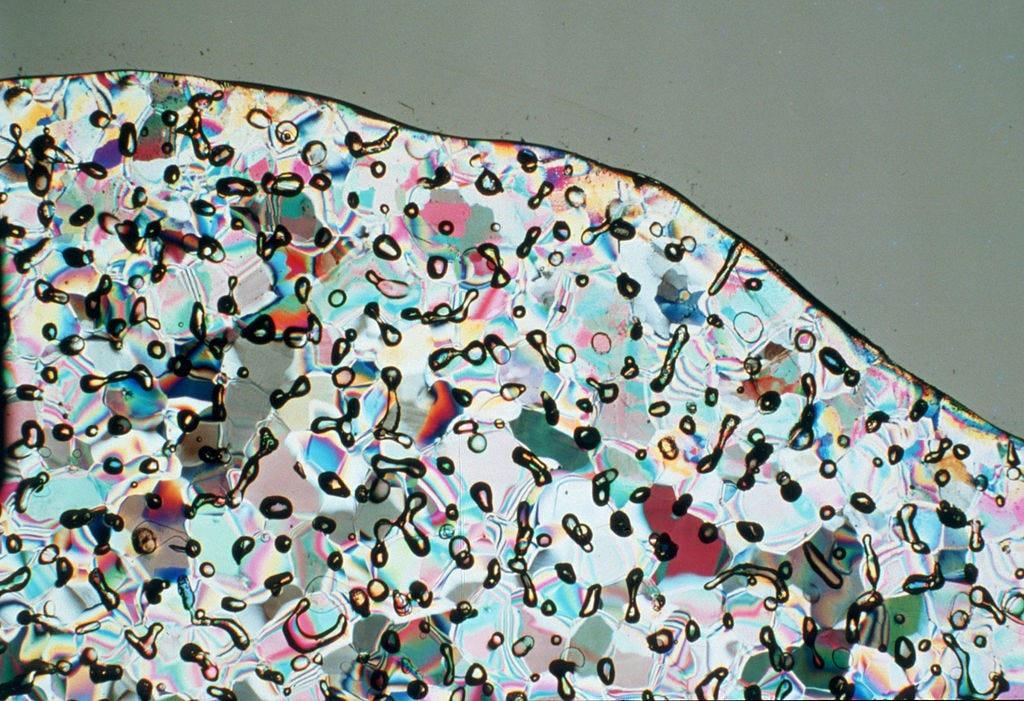

A sliver of Antarctic ice with trapped air bubbles that hold ancient-atmospheric air. These bubbles provide vital information about past levels of greenhouse gases in the Earth's atmosphere. [Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0, CSIRO]

Trapped air bubbles in an ice core illuminated with polarized light. [Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0, CSIRO]

We should ask ourselves, is the speed with which carbon dioxide (CO₂) has risen in the modern atmosphere unprecedented? To answer this question, let’s look at a time period in the geologic record with exceptionally fast CO₂ rise - at the end of the last ice age. At this time, upwards of 20,000 years ago (20 ka on the plots above) - long before humans became technologically powerful enough to dramatically change the chemistry of the atmosphere - it took 7,000 years for CO₂ levels to rise by 80 parts per million (ppm). Because of the burning of fossil fuels by humans, CO₂ levels have recently risen by that same amount in just 55 years, more than 100 times faster than during the end of the last ice age. CO₂ is currently growing at a rate of about 2 ppm per year. We are living in unprecedented times!

To summarize:

1) Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is cumulatively the strongest greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. I will discuss other greenhouse gases, like methane, in future posts.

2) CO₂ levels are higher than they have been in at least 3.6 million years, long before humans evolved on Earth.

3) Compared to natural variability (not related to human-industrial activity), CO₂ is rising faster than ever before, by a lot.

The carbon dioxide (CO₂) data from the NOAA air sampling network and from ice cores has been used to create what I think is one of the most consequential and most important data visualization in climate science. You can see it below, or here. The creation of this video comprises countless careers of scientists and 10s of millions of dollars of research investments.

Time history of atmospheric carbon dioxide from 800,000 years before present until January, 2009 (now somewhat outdated). [NOAA CarbonTracker]

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading.

*** And please, to keep this newsletter going, would you sign up for a paid subscription today. It’s really not that much money to have great science delivered straight to your face. ***

Sincerely,

TRJ, PaleoClimate Scientist who loves ice cores