Uncharted Climate Territory

In the coming decades, global climatic conditions are expected to be outside the range that most living species have ever experienced.

We can view climate change and its effects on living things in absolute or relative terms. In absolute terms, we can consider climate change over the long arc of Earth’s entire 4.54 billion year history. In relative terms, we can consider climate change over the arc of human evolution, considering all that has happened since our ancient ancestors evolved in Africa millions of years ago.

Let’s first consider absolute climate change. Compared to today, we know that the Earth has been warmer or colder in the past - by a lot. Over the last 4.54 billion years, the Earth has alternated between hothouse and icehouse conditions, and even stages known as snowballs.

A hothouse Earth corresponds to periods of time when there is no ice on Earth’s surface. The most recent hothouse Earth occurred about 50 million years ago. In one study of the early Eocene (around 52–53 million years ago) on Ellesmere Island in Canada's High Arctic (79°N), there is evidence for “lush swamp forests inhabited by turtles, alligators, primates, tapirs, and hippo-like Coryphodon”. The temperature never went below freezing - implying no ice - in sharp contrast to the frozen tundra and glaciated landscape on Ellesmere Island today. Overall, it is thought that Earth has been a hothouse 80% of the time.

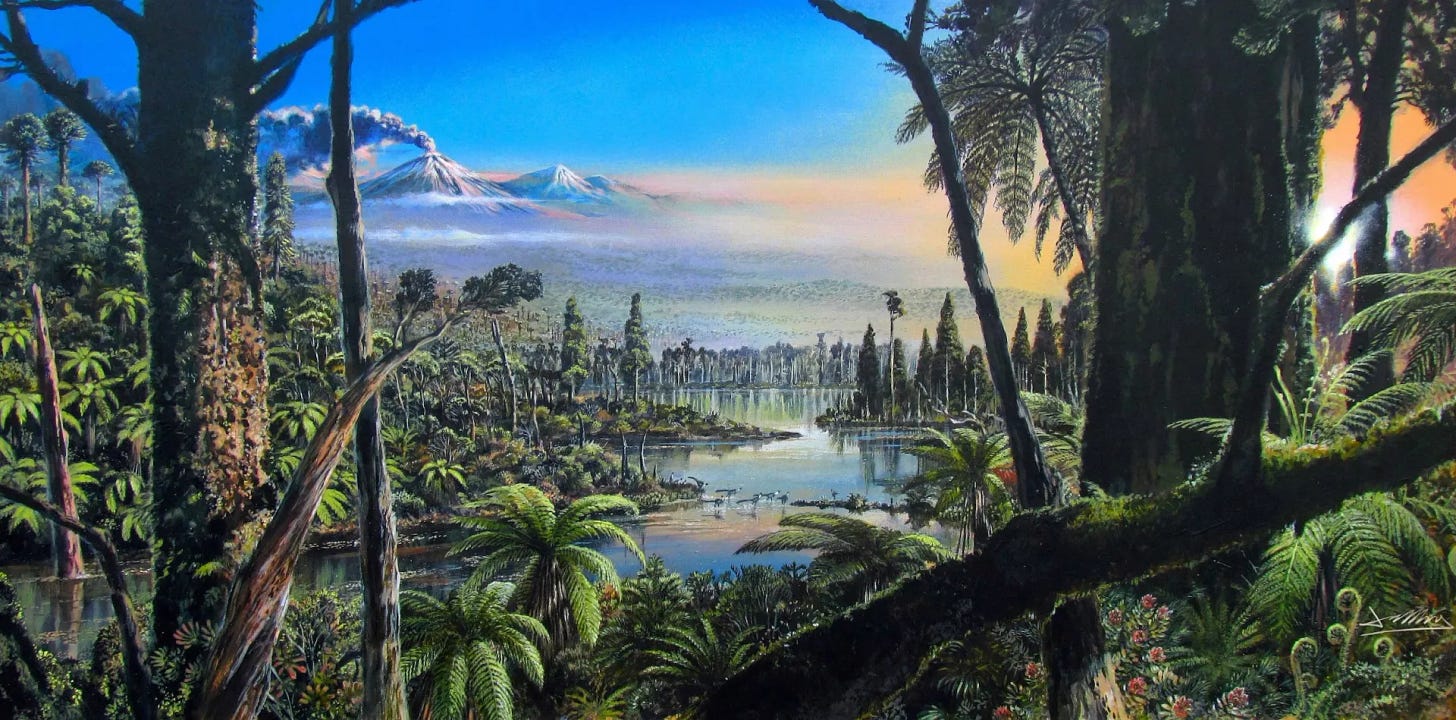

An artist’s illustration of West Antarctica about 90 million years ago. At this time, a temperate rainforest thrived during a hothouse climate. Dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. Our human-like ancestors would not evolve for another 88 million years. [image credit: McKay/Alfred Wegener Institute, CC-BY 4.0].

An icehouse Earth corresponds to periods of time when ice is present on Earth’s surface. During an icehouse Earth, atmospheric greenhouse gases tend to be less abundant, and temperatures tend to be cooler globally. The Earth is currently in an icehouse stage because ice sheets are present at both poles in Greenland and Antarctica, not to mention the many other forms of ice like mountain glaciers, tropical ice caps, and sea ice.

Blue ice covering Lake Fryxell in the Transantarctic Mountains. [Wikipedia, Joe Mastroianni/National Science Foundation, Public Domain].

A boat sailing in the Ilulissat Icefjord, western Greenland. The fjord connects with the Jakobshavn Glacier, which drains 6.5% of the Greenland ice sheet and produces around 10% of all Greenland icebergs. [Wikipedia, Greenland Travel, CC BY 2.0].

A Snowball Earth is a period of time when the Earth’s surface became entirely or nearly entirely frozen. A frozen Earth, in theory, would prevent sunlight from reaching organisms under the ice, stopping the photosynthetic process and leading to the extinction of life. The fossil record proves otherwise - life persisted! One study, “Thickness of tropical ice and photosynthesis on a snowball Earth”, suggests that the thickness of tropical ice cover would not have exceeded 10 meters, allowing just enough light to penetrate to the ocean below for the (precarious) survival of eukaryotic algae. The last Snowball Earth ended around 635 million years ago when complex life was just beginning to develop.

An artist's rendition of a fully-frozen Snowball Earth with no remaining liquid surface water. [Wikipedia, Oleg Kuznetsov, CC BY-SA 4.0].

Alright, so we know in the distant past, Earth was very warm with no ice on the surface of the planet (most recently 50 million years ago), and in the more distant past, Earth was completely frozen over (most recently 635 million years ago). How does any of this relate to our current climate change predicament? The short answer is that it doesn’t, unless you view the situation in relative terms.

One question we can ask ourselves is how long have humans been around on Earth, and what climate conditions have our distant ancestors experienced? In the fossil record, the first of our ancestors that sort of looked like us and moved like us was Homo erectus (H. erectus), Latin for upright man. In 1974, scientists in East Turkana, Kenya found one of the oldest pieces of evidence for H. erectus, a small skull fragment that dates to 1.9 million years before present. This is our starting point - how has climate change varied over the last few million years for our human-like ancestors, and are we now entering uncharted climate territory?

Photo of a Homo erectus reconstruction at the Natural History Museum, London. [Wikipedia, Werner Ustorf, CC BY-SA 2.0].

There is one particular study that is highly pertinent to this discussion, “The Future of Species Under Climate Change: Resilience or Decline?”, published in the journal Science. This paper opens with the following quote:

As climates change across already stressed ecosystems, there is no doubt that species will be affected, but to what extent and which will be most vulnerable remain uncertain. The fossil record suggests that most species persisted through past climate change, whereas forecasts of future impacts predict large-scale range reduction and extinction.

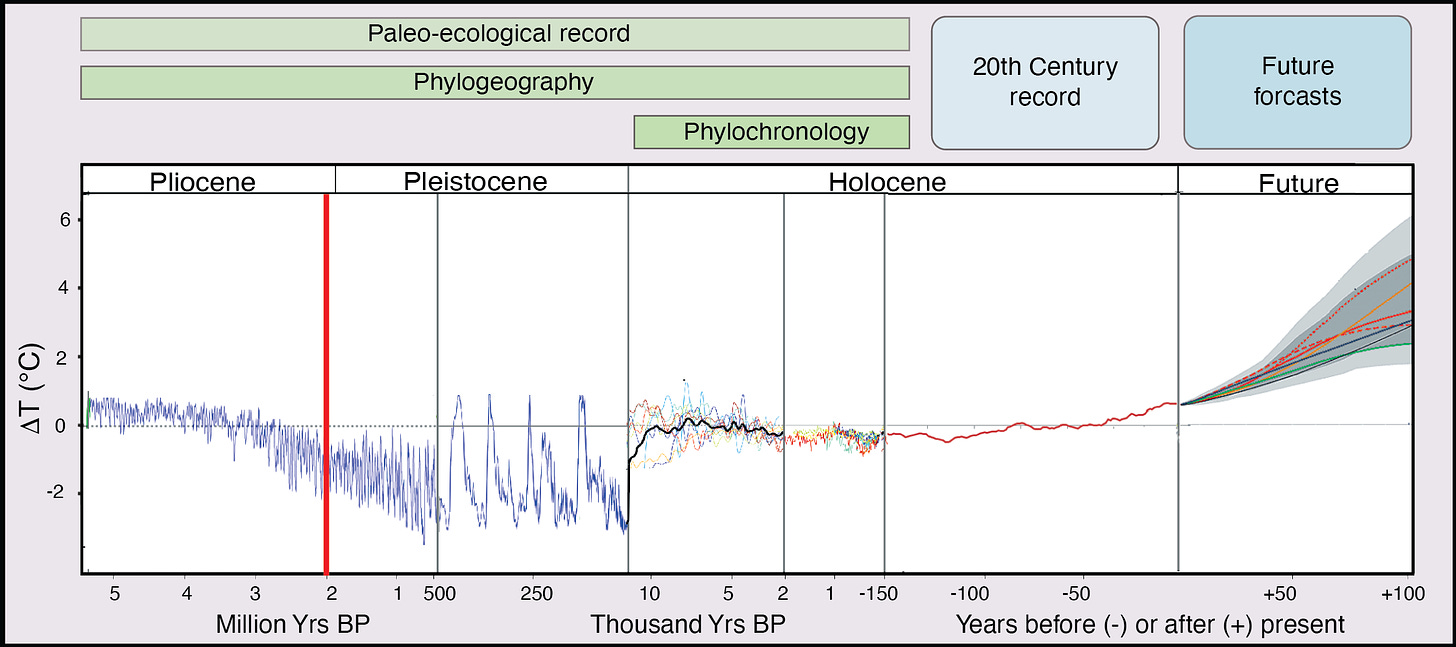

How unprecedented is our current situation? The following plot of temperature changes over the last 5 million years, as well as future temperature projections, provides a very clear answer.

The figure shows global mean temperate changes (ΔT) relative to the year 1950, which is set to ΔT = 0°C. The x-axis has different scalings (millions of years, thousands of years, and years) for time before present (BP) and the future. As an example, about 12,000 years ago, the global mean temperature of Earth was almost 4°C colder than the present, whereas 125,000 years ago Earth was just barely warmer than today. The thick red line indicates when Homo erectus - an ancient ancestor of humans - appears in the fossil record. [Figure from Moritz and Agudo, 2013, future temperature projections from Jansen et al. 2007, newer projections are available].

The absolute best summary of the above figure is given in the report, “Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises”, published by the National Academies Press.

Global climatic conditions by 2050 to 2100 are expected to be outside the range that most living species have ever experienced.

That statement stops me in my tracks. It leaves me speechless. The first time I ever read that statement, I truly began to understand the seriousness of our current climate situation. Another quote from “The Future of Species Under Climate Change: Resilience or Decline?” sums up my thinking on this topic:

As we move into climate conditions without recent parallel and across ecosystems already strongly affected by humans, the challenge is to increase resilience of natural systems now, in conjunction with continuing research to improve our capacity to predict vulnerability. These priorities must undoubtedly be accompanied by the urgent mitigation of the main culprit, the greenhouse gas emissions.

And that is simply the best path forward: urgent mitigation of the main culprit, the greenhouse gas emissions, which continue to rise due to human activity.

To answer the central question of this post - have we entered uncharted climate territory? For most living species, including humans, the answer will be yes in a few decades, and for some species, the answer is already yes. While humans are astoundingly resilient, many other creatures will likely go extinct. That alone is enough reason to take immediate action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and for that matter, reducing environmental degradation and pollution. Luckily, we have the ability to do these things, while also improving our quality of life at the same time!

To conclude this post, please enjoy the trailer above for the movie “Ice Age: The Meltdown”, filled with amazing quotes, and if you listen carefully at the end, a subtle inclusion of the song “I Melt With You”, originally by Modern English, covered by Bowling for Soup. Check out the throwback music video below. Definitely listen to the kazoo at 2 min 01 sec!

Thanks for reading this installment of Paleoclimate. If possible, please support this newsletter with a paid subscription, possibly as a gift for friends and family. It’s really quite cheap, and you will be supporting future articles about Paleoclimate science and pop-culture.

All the best,

TRJ, PaleoClimate Scientist

p.s. - You’ve seen the difference, and it’s getting better all the time!

Thank you to the readers who pointed out a typo and a grammatical error. Those are fixed now.