Polar Ice Cores, Part 2: The Ice Ages

Gargantuan, towering, and immense ice sheets have partially swallowed Earth many times in the past.

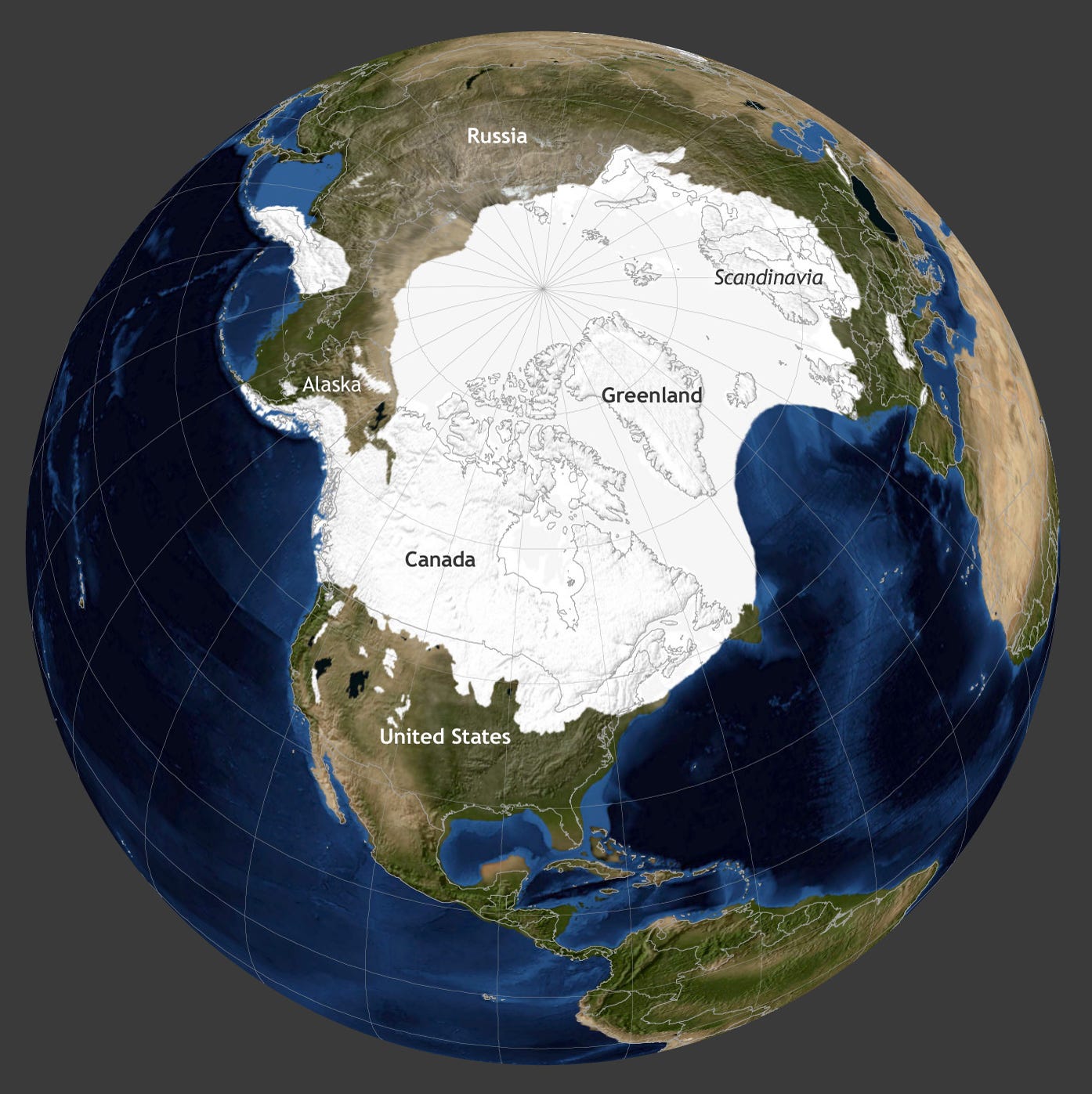

At the maximum extent around 20,000 years ago, large ice sheets covered most of Canada, parts of Alaska, all of Scandinavia, parts of northern Europe and Switzerland, large tracts of northern Russia, mountain ranges in Peru and Tibet, the Chilean Andes including the entire southern tip of South America, and other places like parts of New Zealand’s southern island and many tropical ice caps around the world. Interestingly, locations that would become major cities thousands of years later - Juneau, Vancouver, Seattle, Chicago, Toronto, Montreal, New York City, Boston, London, Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki, Moscow, and many others - were covered by ice that would dwarf present day skylines. At the height of glaciation, the vast stores of ice on land dramatically lowered sea level by 100s of feet, opening the Bering land bridge that permitted migration of humans to North America from Siberia.

A map of ice sheets 19,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice spread over much of North America and Eurasia. Notice the Bering land bridge connection between Alaska and Russia. [NOAA Climate.gov]

Evidence for glaciation is scattered around the world, some of which is hiding in plain site. Let’s take a look at the United States. In the last ice age, a sheet of frozen water, known formally as the Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets, formed over North America, reaching a maximum depth of more than two miles. The southern edge of the ice sheet extended into what is today the northern United States. At the edge of the ice sheet, a terminal moraine formed, which is a ridge of debris pushed into place by the ice like a bulldozer. Moraines can be 100s of feet tall. Evidence for last glacial moraines run intermittently along the entire United States, from the Puget Sound in coastal Washington and the Withrow Moraine in central Washington, to the Tinley Moraine near Chicago and the Kettle Moraine in Wisconsin, to the Outer Lands moraines in New England, comprising the peninsula of Cape Cod and the islands of Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, the Narragansett Bay Islands, Block Island, Long Island, and Staten Island, as well as surrounding islands and islets.

The terminal moraine (the dark arcing line of debris at the ice edge) of Wordie Glacier, Greenland. The largest terminal moraines are formed by major continental ice sheets and can be over 300 to 400 feet in height. [Wikipedia, Public Domain, NASA/Michael Studinger]

The Withrow Moraine in Douglas County, central Washington, which to the casual passerby would appear to be a small rolling hill, but also happens to be evidence of a massive glaciation event during the last ice age. [Wikipedia, Public Domain]

Another bit of glaciation evidence hiding in plain site are glacial erratics, which are strange rocks that sit upon the landscape like alien visitors, completely different than the type of rocks native to the area. These erratics were transported long distances by slow-moving glaciers and then deposited after the ice melted or receded away. Similarly, glacial tills and extremely fine glacial flour are left behind. Glacial till contains sediments of every size, from tiny particles to large boulders, all jumbled together. Glacial flour is smaller than a grain of sand and is responsible for the milky water in rivers, streams, and lakes that are fed by glaciers.

Glacial erratic boulder in Discovery Park, Seattle, Washington, dropped in place by a glacier long ago. [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, Dennis Bratland]

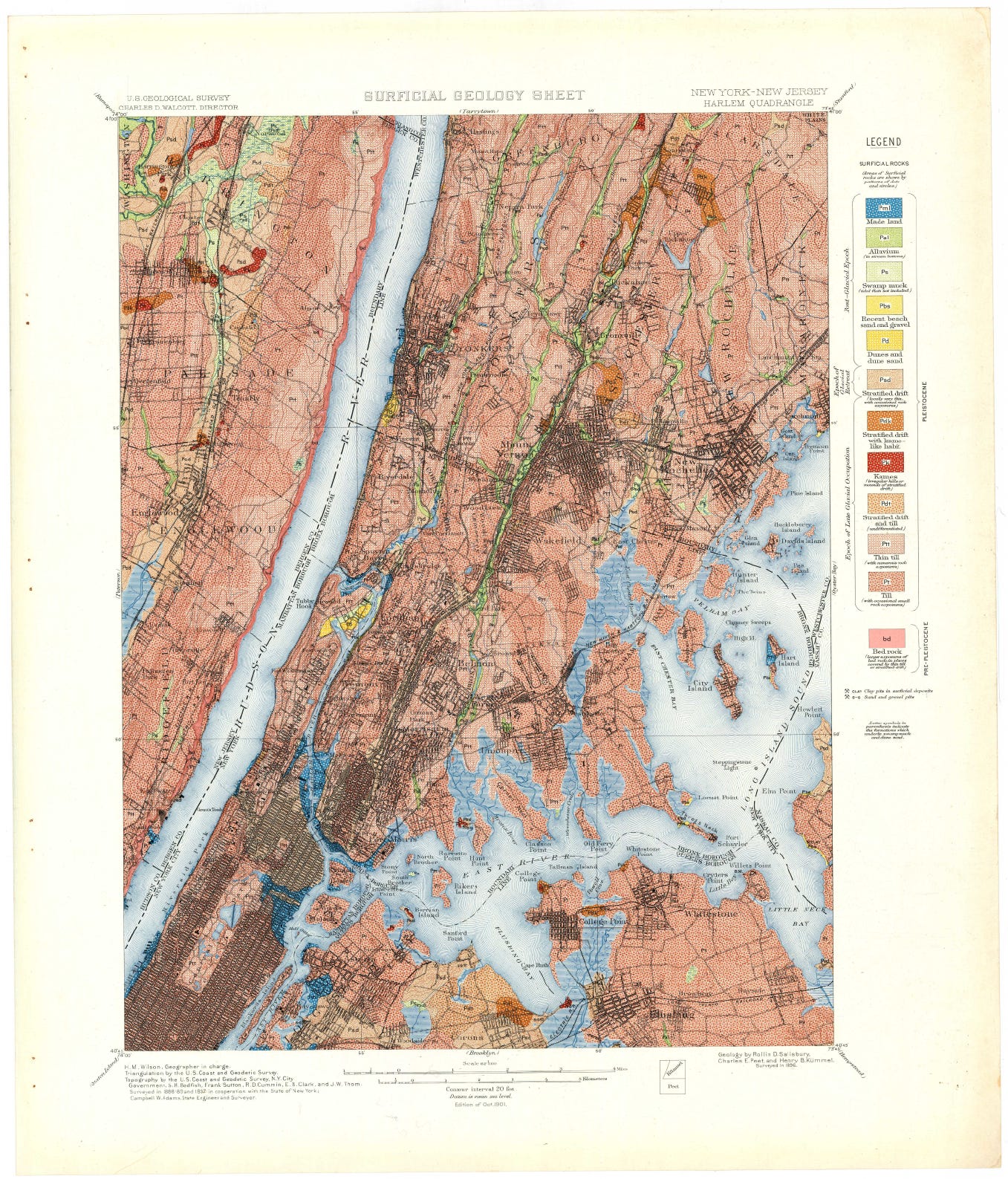

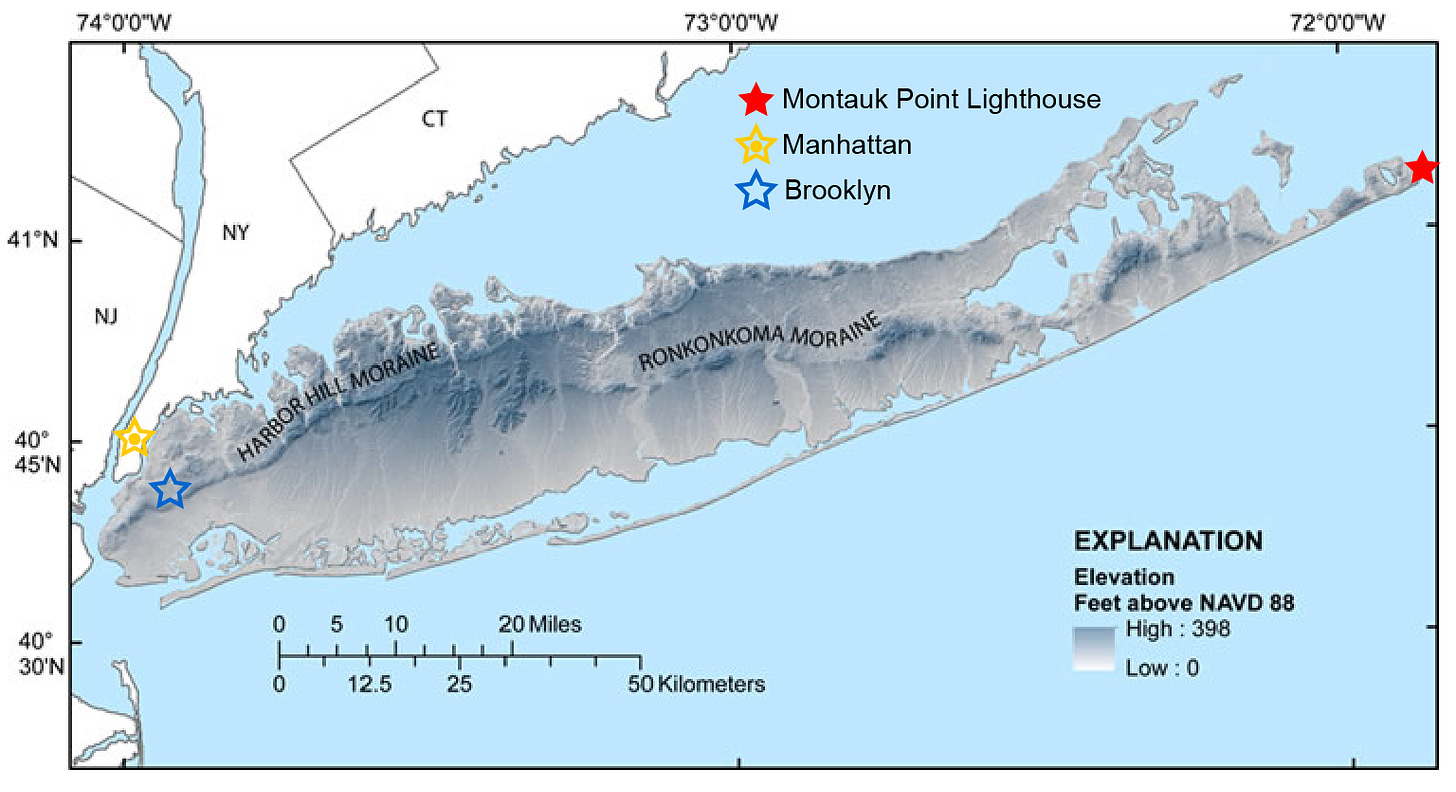

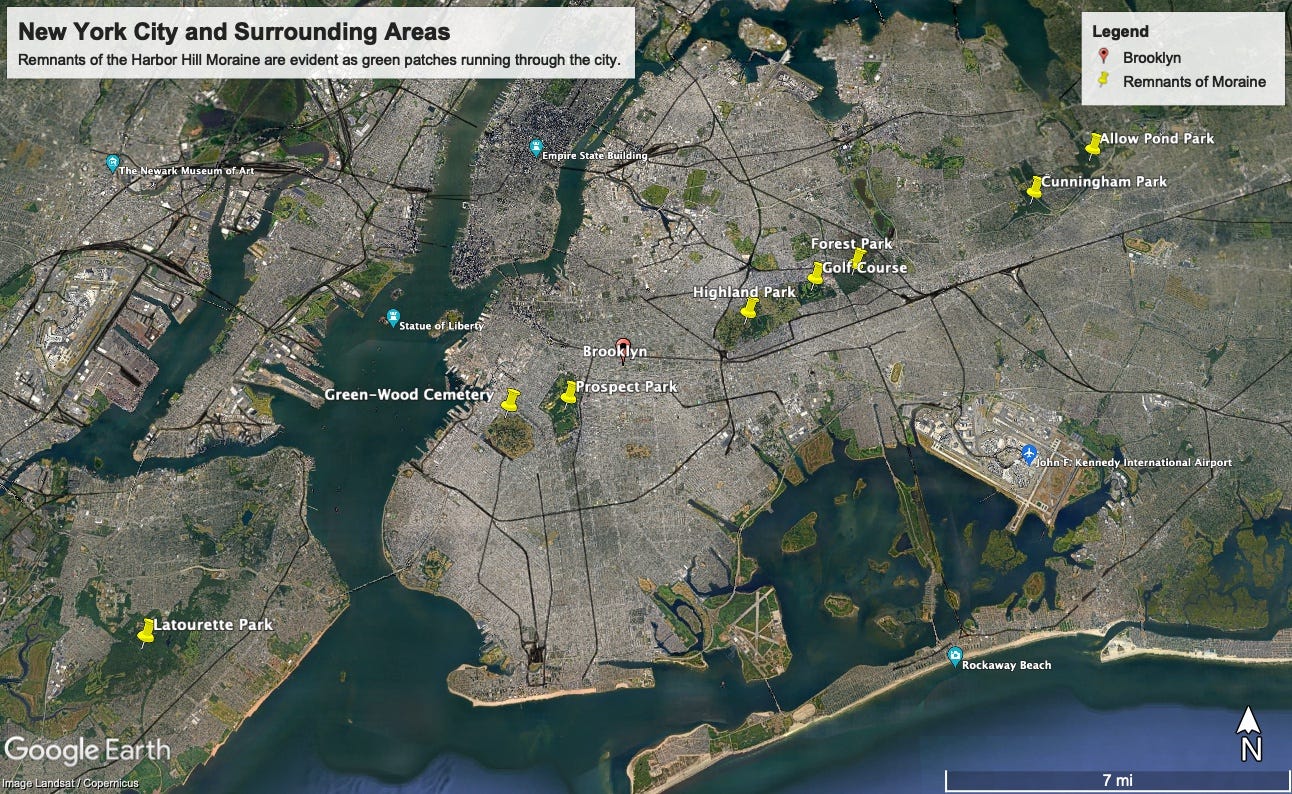

One of the best places to find evidence of past glaciation is actually in the most populous city in the United States, New York City, as well as nearby Long Island. As early as 1902, the U.S. Geologic Survey documented that most of the New York City area was underlain with glacial till and multiple moraines were left behind when the Laurentide Ice Sheet receded. They published their findings in a large folio (an example is shown further below), which is also a wildly beautiful scientific work of art. On the far eastern tip of Long Island, the Montauk Point Lighthouse sits atop remnants of the Ronkonkoma Moraine, and nearby ocean waves are constantly eroding sea cliffs exposing glacial till. The Harbor Hill Moraine (slightly younger than the Ronkonkoma Moraine) runs along the North Shore of Long Island as well as through present day Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. The Harbor Hill Moraine, filled with glacial till, was a major problem for engineers seeking solid ground for building foundations in the early days of construction in New York City. As a result, building planners relegated the elevated remnants of the moraine to cemeteries, parks, and golf courses, evident in satellite imagery (see further below) as a green-line weaving through the city

During the last ice age, the Laurentide Ice Sheet sat on top of present day New York City, and rose hundreds of feet higher than the tallest buildings. [Above: view towards Central Park, flickr, CC BY 2.0, Javier Morales. Below: Times Square, Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, Terabass]

Quad 2 in the U.S. Geologic Survey New York City folio of Paterson, Harlem, Staten Island, and Brooklyn quadrangles, New York-New Jersey. [U.S.G.S. Folios of the Geologic Atlas 83. By: F.J.H. Merrill, N. H. Darton, Arthur Hollick, R.D. Salisbury, Richard E. Dodge, Bailey Willis, and H.A. Pressey]

Map of Long Island topography (elevation above NAVD 88) and glacial moraine locations. The Ronkonkoma and Harbor Hill Moraines sit as high as 400 feet above surrounding areas. [Wikipedia, Public Domain, U.S. Geologic Survey; updated to include landmarks]

The Montauk Point Lighthouse at dawn, which sits on or near remnants of the Ronkonkoma Moraine. [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, Ronald Diel]

Google Earth image of the New York City region. Remnants of the Harbor Hill Moraine can be traced by following the arcing line of green-spaces through the city, denoted by the yellow pins. [Google Earth]

North of the Harbor Hill Moraine, Central Park is filled with interesting geology related to the last ice age. Glacial erratics are found throughout the park, the two best examples can be found at The Pool (West Side between 100th and 103rd) and Heckscher Playground (Mid-Park between 61st and 63rd). Next to the playground is Umpire Rock (West Side at 63rd), named for the meadow where children used to play baseball. Umpire Rock is covered in glacial striations, scratches or gouges cut into bedrock by glacial abrasion. To learn more, check out this amazing Field Guide for the Geology of Central Park and New York City by the American Museum of Natural History.

A view of Umpire Rock looking across Heckscher Playground, and a close-up of the glacial striations in the rock. [above: flickr, CC BY 2.0, edenpictures. below: flickr, CC BY 2.0, Web-Betty]

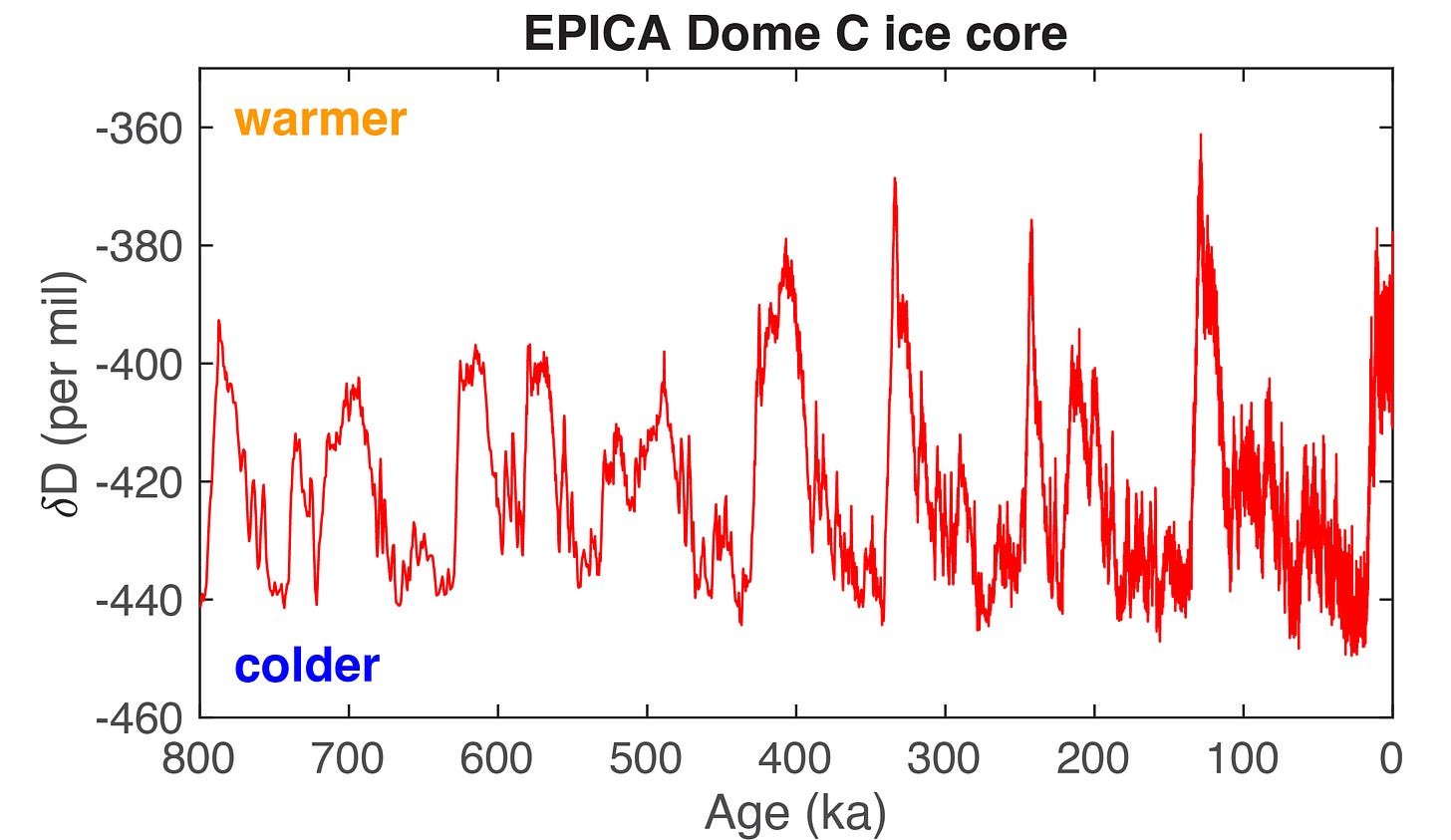

The growth and recession of large ice sheets has been a monumental occurrence in Earth’s past. A good question to ask is this: how many times has this happened? If we look at ice core records from East Antarctica, we can examine how Earth’s climate has changed over the last 800,000 years. We find that ice-age cycles occur about every 100,000 years, with about 90,000 years of colder and icier conditions, punctuated by about 10,000 years of warmer climates where ice sheets recede dramatically. Human civilization arose in the the most recent warm climate, known as the Holocene.

A record of hydrogen isotopes (δD) from the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) Dome C ice core from East Antarctica, extending over the last 800,000 years (the ‘ka’ on the x-axis refers to ‘thousands of years before present’). The δD measurement can be considered a proxy for local temperature. On the right side of the plot is year 0, corresponding to the current warm period in which we live, whereas from 115-12 ka (115,000 to 12,000 years before present) the Earth experienced a long ice age. [data: Pangaea; plot: Tyler R. Jones, CC BY 4.0]

Let’s not forget, through all of these ice ages, and through all of the major changes and upheavals in the climate system as the Earth warmed and cooled, and as the ice sheets grew and shrank, humans were evolving - we are quite the resilient species!

Until next time, please consider supporting this newsletter and sharing it with whoever might be interested. A lot of hard work goes into these posts, so if you are willing, please consider a paid subscription as well.

Sincerely,

TRJ, PaleoClimate Scientist (and enormous fan of ice)