Polar Ice Cores, Part 1: Undercover Science

The early history of ice-core science is largely intertwined with covert military operations.

Earth’s two great ice sheets hold secrets about past climate. Both the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Ice Sheet are miles thick, comprised of layers of snow that compressed into ice over many 100s of thousands-to-millions of years. Those icy layers preserve chemical signatures of past climate, which scientists can access using custom built drills to extract meter-long cylinders of ice known as ice cores. The longest sets of ice cores extend more than two-miles in length, prompting the popular saying “two-mile time machines”. And really, I would say ice cores are the closest thing we have to time machines, allowing us to peer into the past in high-detail and understand the climatic conditions humans experienced during the course of their evolution from hunter-gatherers to powerhouse-species that dominate the planet.

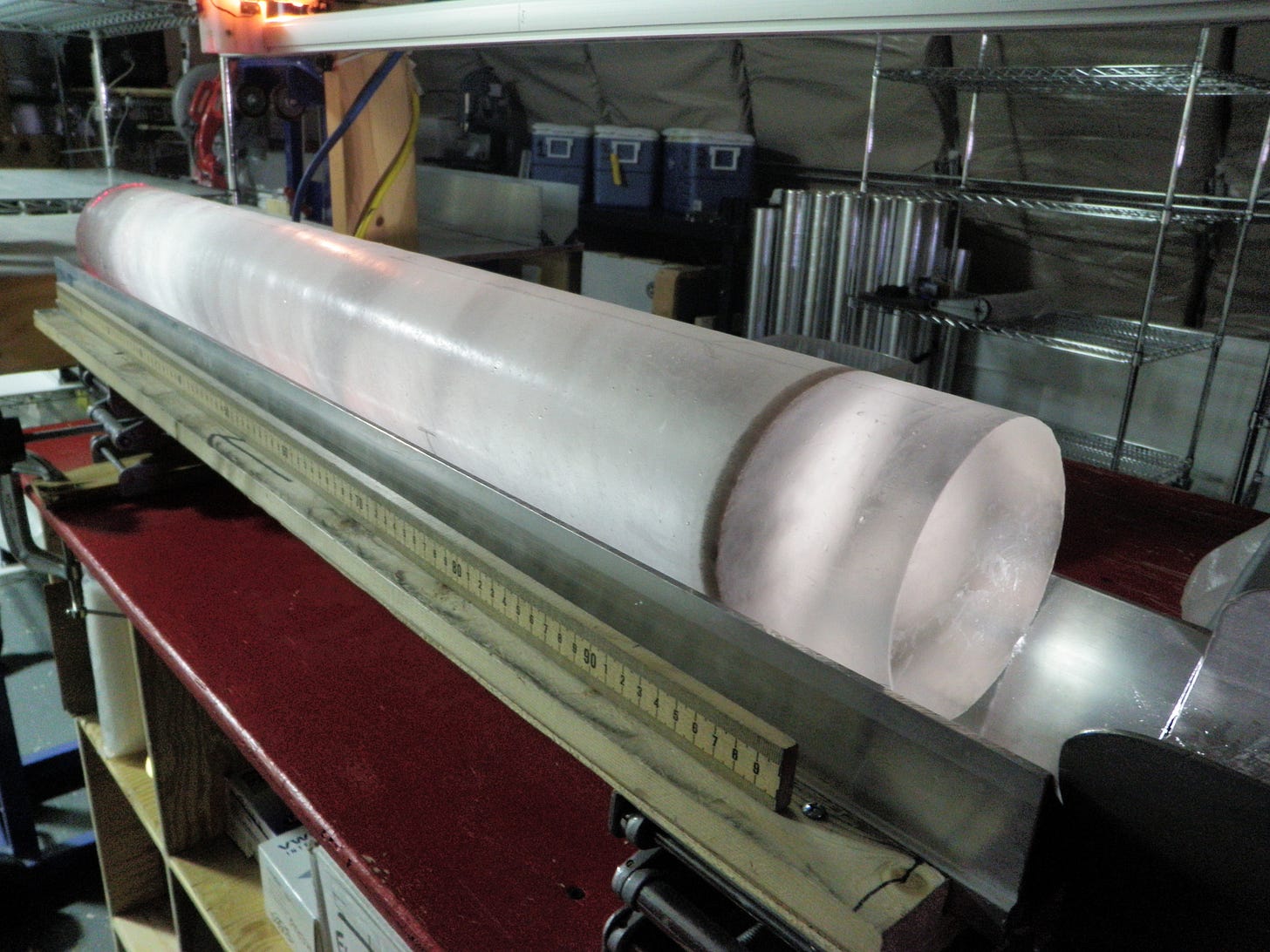

A one-meter long section of ice core recovered from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), as part of the WAIS Divide ice core project. The oldest ice core from WAIS Divide dates to about 68,000 years before present. The dark layer in the ice is caused by an ancient volcanic eruption that blanketed the ice sheet in ash. [WAIS Divide ice core gallery, photo: Heidi Roop]

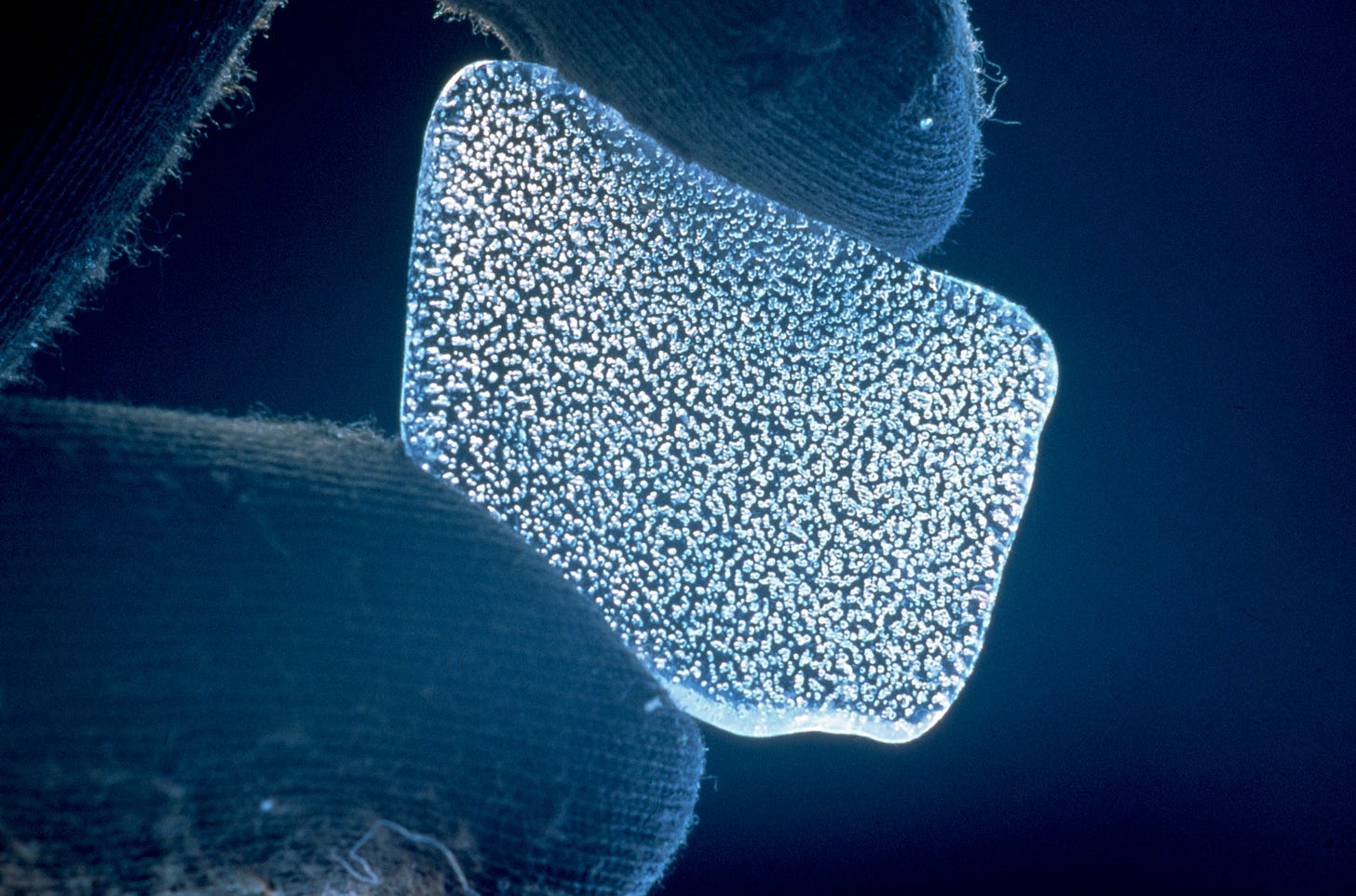

A sliver of Antarctic ice with trapped air bubbles that hold ancient-atmospheric air. These bubbles provide vital information about past levels of greenhouse gases in the Earth's atmosphere. [Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0, CSIRO]

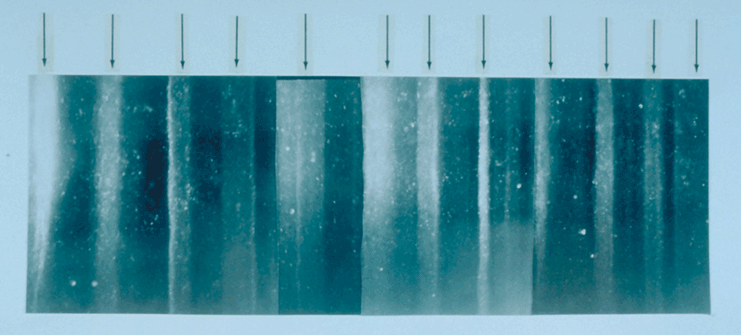

An illuminated, 19-centimeter section of GISP2 ice core (central Greenland) from 1,855 meters depth. The section contains 11 annual layers, with summers marked by arrows and winters in between. [Wikipedia, Public Domain]

A human-made ice cave for scientific research in northwest Greenland, part of the North Greenland Eemian Ice Drilling (NEEM) project. Here, an ice-core drill is in a horizontal position, allowing ice to be extracted from the core barrel. The drill is then flipped vertically and lowered into the ice sheet with a cable and winch to extract the next section of core. As deeper and deeper depths are reached, lowering and raising the drill can take many hours. [NEEM ice core gallery, Sepp Kipfstuhl]

A fresh ice core being extracted from a core barrel. [NEEM ice core gallery, Sepp Kipfstuhl]

Using ice cores, scientists can reconstruct things like temperature, snow accumulation rates, atmospheric greenhouse gases, volcanic eruptions, dust, sea salts, black carbon (often from fires), and so much more. There have been and currently are ice core camps operating in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as many other places, such as tropical ice caps and mid-latitude ice fields. Each location offers a unique viewpoint into past climate.

The early history of polar ice coring, dating back to the 1950’s, is largely intertwined with often-covert military operations, and in my view, undoubtedly deserves its own set of modern Hollywood movies, possibly as a spy-meets-scientist thriller series. Here are four examples of the exciting history of ice core science:

Camp Century, northwest Greenland: A highly-secretive subsurface military-research station established in 1958 by the U.S.A., whose end goal was to install a vast network of nuclear-missile launch sites that could survive a first strike. At least 32 buildings and 21 tunnels were installed under the ice sheet, creating a subterranean layer close to the north pole that feels like a plot line straight out of a comic book. In 1966, the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) used an early ice-core drill to penetrate miles of ice, recovering the first deep ice core and sub-ice sheet soil samples in the world. To this day, the project is still yielding scientific discoveries.

An ice core drill in Camp Century's subterranean ice tunnels. [Photograph by David Atwood, U.S. Army-ERDC-CRREL, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives]

Byrd Station, West Antarctica: The same ice-core drill used at Camp Century next went half-way around the world to Byrd Station, where a 2,164 meter ice core was drilled from 1966 to 1968. The station is named for Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957), an American naval officer and pioneering aviator, polar explorer, and organizer of polar logistics. His ancestors include John Rolfe and his wife Pocahontas. On November 28, 1929, Byrd embarked on a mission to achieve the first flight to the South Pole and back, which launched from the Little America I exploration base on the Ross Ice Shelf (nearly at sea level), in the Pacific-sector of coastal West Antarctica. During the flight Byrd, along with pilot Bernt Balchen, co-pilot/radioman Harold June, and photographer Ashley McKinley, were forced to dump empty gas tanks and emergency supplies so their plane could reach the altitude of the Polar Plateau (average elevation 9,800 ft) where the South Pole is located. The crew accomplished their mission in 18 hours, 41 minutes. As a result of this achievement, Byrd was promoted to the rank of rear admiral by a special act of Congress on December 21, 1929; he was 41 years old, making him the youngest admiral in the history of the United States Navy.

The movie poster for ‘With Byrd at the South Pole’ (1930), a documentary film about Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd and his aviation quest to reach the South Pole. [Wikipedia, no copyright markings]. The film won Best Cinematography at the 3rd Academy Awards, becoming the first documentary to win an Oscar. Hundreds of mid-20th century magazines, books, and other print media and a handful of films have been made about Richard E. Byrd.

DYE-3, southern Greenland: Between 1955 to 1960, the U.S.A. established fifty-eight Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line radar stations across Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Iceland at a cost of billions of dollars. The aim was to watch over northern air spaces 24-hours a day to warn of possible Soviet aircraft en-route to attack the U.S.A. In 1971, using funding from the National Science Foundation, an ice-core drill was installed 25 meters below the ice surface at the bottom of one of the massive columns supporting the radar station. An initial shallow ice core was drilled to 372 meters depth, and later in 1979 to 1981, a deep ice core of 2,037 meters was drilled.

DYE-3 circa 1982, prior to DEW Line deactivation. The drilling and recovery of ice cores has occurred at the bottom of one of the massive supporting arms of the radar system. [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, G. Trent]

Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, Antarctica: The fact that we have a science station in one of the most inhospitable corners of the planet is a testament to human ingenuity. The station is the only year-round inhabited place on Earth from which the Sun is continuously visible for six months followed by six months of darkness. The original Amundsen–Scott Station was built by Navy Seabees (United States Naval Construction Battalions) for the U.S.A. federal government in 1956, as part of its commitment to the scientific goals of the International Geophysical Year, including study of the geophysics of the polar regions of Earth. More than 60 years later, the South Pole Ice Core (SPICEcore) project reached its final depth of 1,751 meters on January 23, 2016.

Aerial view of the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, February 5, 2009. “The main structure is in the middle. Directly in front of it is the ceremonial pole surrounded by the flags of the original signatory nations to the Antarctic Treaty. To the left is a dome that once housed the previous station. Rows of Jamesway shelters, known as Summer Camp, can be seen to the upper right.” [United States Antarctica Program, Andrew V. Williams]

The oldest continuous ice-core records extend back in time from the present day about 125,000 years in Greenland and about 800,000 years in Antarctica. There has also been multi-million year old ice recovered, such as 2.7 million year old ice in Allan Hills, Antarctica. In three upcoming Paleoclimate posts, I want to share what I consider to be the most important findings from scientific studies of these oldest-ice cores.

The Ice Ages

Variations in Greenhouse Gases

Abrupt Climate Change

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading, and if you can, please consider supporting this newsletter and sharing it with whoever might be interested.

Sincerely,

TRJ, PaleoClimate Scientist

Thanks everyone - I really enjoy writing these newsletters!

I love this mix of science info, natural history and film pics and literature.